Julie Freeman on the importance of interference

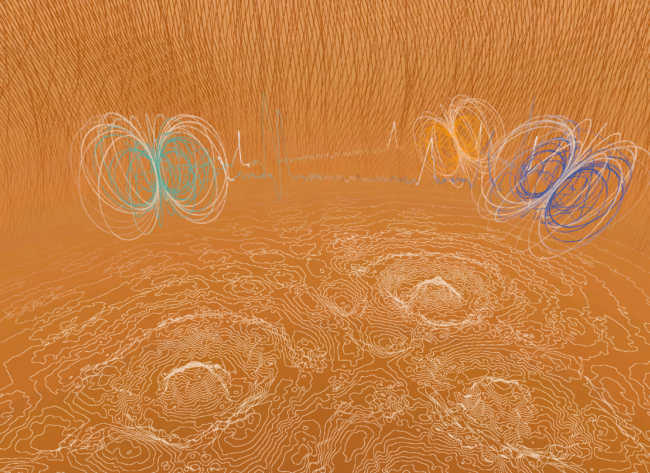

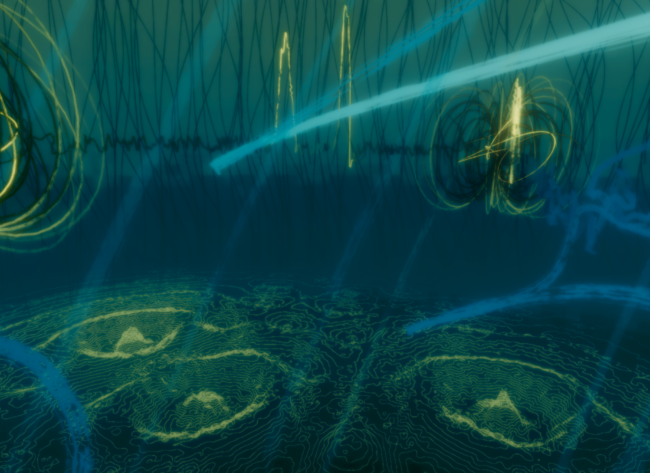

Fri 12 Jul 2019COSMOS 2019 artist, Julie Freeman talks about the inspiration behind the newly commissioned VR experience I̶n̛t͘e͟rf̕e̢ren̵ce, and why interference/interfering can lead to new perspectives and perceptions of what we know.

I̶n̛t͘e͟rf̕e̢ren̵ce is an experimental VR experience. The residency started with site visits to Jodrell Bank and meetings with the scientists. After discussions with Rene Breton, Sally Cooper and Tim O’Brien at Jodrell Bank, it was clear that pulsar detection is core to their work. Two particular aspects of the research stood out for me.

Firstly that the scientists use pulsar data to help them with other measurements* such as measuring the effect of gravitational waves. In this sense, pulsars act as stepping stones to help scientists find out more. This process of using data to generate more data reminded me of Euclid’s original description (from around 300 bce) of a datum as being something that begets more data, ultimately helping us to increase knowledge by incrementally pushing toward the unknown.

Capturing audio over @jodrellbank with #COSMOS19 artist @joz_freeman and @ArupUKIMEA for our immersive VR experience being showcased @bluedotfestival this July. Thanks @ProfTimOB for letting us behind the scenes in the Observatory pic.twitter.com/nKNsaYLEG7

— Abandon Normal Devices (@ANDfestival) June 7, 2019

Secondly, I found the collaborative nature of the radio astronomy field not just remarkable, but also admirable. The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project is a global initiative that will effectively turn the whole Earth into a radio telescope, and for it to succeed it requires deep collaboration and data sharing. The HQ for the SKA is located at Jodrell Bank, where they will process the data from the remote telescopes, looking for more pulsars and signs of life from other civilisations. At a time when global cooperation is fractious and dwindling, this coming together of a planetary wide community can be seen as an example of what’s possible with a shared goal.

These two elements are woven into the concept of the artwork, players are immersed in a multitude of data points (from pulsar location and rotation frequencies to the sheer volume of the telescope data) all of which create the abstract visual environment that the player ‘interferes’ with. In future versions of the work, players will have to collaborate to create a more complete pulsar map, and reveal other worlds.

The idea for I̶n̛t͘e͟rf̕e̢ren̵ce comes from looking at pulsar hunting scientists who search for abnormal patterns in their data to spot the periodic pulses, indicating new pulsars. Some interference is helpful. To enable multiple telescopes across the world to work as a huge combined one, something called astronomical interferometry uses wave interference to cancel duplicate signals and leave a useful dataset behind. They listen to the cosmos using radio telescopes to locate dying neutron stars which appear to emit a pulse of light as their magnetic cores keep them spinning in space. The scientists use algorithmic techniques to hunt through the vast amounts of data collected for tiny repetitive patterns. Inside the pulsar, time, space, light and sound all change creating a world within a world and meddling with our expectations of physics.

Thinking about the potential of VR, I’ve become curious about the sonic possibilities of this immersive technology – of placing highly directional sounds within an ambient soundscape, and having the ability to move those sounds in ways which are physically impossible in the non-virtual world. I started wondering how would it feel to be in a novel sonic space which contests our preconceptions? Together with Kuva, and ARUP’s SoundLab in Manchester, we are testing an approach to sound which takes its origins in musique concréte (mixing sounds sampled from real world recordings) with some influence from dub reggae. In the experience, both directional and ambisonic sampled sounds are placed in a navigable space, composed only minimally by proximity. We’ve used transposed pulsar data to create bass rhythms and field recordings from Jodrell Bank’s data processing labs for ambient noise and sound samples. The playback control is in the hands of the player, who can trigger sounds in response to actions.

In I̶n̛t͘e͟rf̕e̢ren̵ce players are asked to listen out for signs that a pulsar might exist, as they move toward the sound, a pulsar appears giving them access to see and hear a shifted world. The more pulsars discovered, the closer the player gets to the final reward.

Currently, the work is at proof of concept stage. Ultimately I̶n̛t͘e͟rf̕e̢ren̵ce will be a collaborative multi-player experience. We are looking for players to test the experience – come and find us in the Mission Control tent at bluedot 2019.

* “The main goal of Pulsar Timing Arrays, which aim to detect gravitational waves with pulsars, is measuring the amplitude of background gravitational waves caused by a history of supermassive black hole mergers. It is a key issue in understanding how our Universe has evolved, in particular how galaxies merged and grew over time and got to form supermassive black holes. It will also be able to detect individual merge events of binary supermassive black holes in the distant Universe.” (from Dr Rene Breton, Reader in Astrophysics at The University of Manchester)

All images are in experience shots taken from I̶n̛t͘e͟rf̕e̢ren̵ce.

Find out more about I̶n̛t͘e͟rf̕e̢ren̵ce here.

Follow our journey #COSMOS19.

I̶n̛t͘e͟rf̕e̢ren̵ce created by Julie Freeman, as part of COSMOS, the international artists commission and residency for the Lovell Telescope. Produced by Abandon Normal Devices, commissioned by Jodrell Bank Observatory, Abandon Normal Devices and Cheshire East Council as part of SHIFT. Supported by University of Manchester, bluedot, Arup, Kuva, with public funds from Arts Council England (ACE) and CreativeXR, a joint collaboration between Digital Catapult and ACE.

Recent Journals

- A Gig at Sunrise: Reflecting on W Brzask at Ephemera Festival

- Announcing our THREE FIELDS artists

- New Rhythms

- Introducing Commons // Keiken and Jazmin Morris

- Introducing our Creative Associates programme

- Reflections on the Associate Board Member Programme

- The Future of Arts Governance

- Rendering our virtual, net and digital discourses

- Announcing a new partnership between AND and the School of Digital Arts

Other Journals

-

2025

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

2019

-

2018

-

2017

-

2016

-

2015

-

2014

-

2013

-

2012

-

2011