Digital Dark Ages: Speculations on Digital Decay by Patrizia Costantin

Sun 17 Sep 2017‘‘The world is suffering from a dark and silent phenomenon known as ‘digital decay’ – anything stored in computerized form is vulnerable to breakdown and obsolescence.’’

Bruce Sterling (2004)

The above quote by Bruce Sterling concisely summarises the widespread understanding of digital decay as a process that only affects the immaterial data stored, shared and uploaded on the Internet. A quick Google search on ‘Digital Decay’ confirms that it is a topic that belongs to the field of digital preservation and heritage: data, file and all the immaterial information that has been produced in digital format is at risk under the threat of digital decay.

As part of this year’s AND Festival, the exhibition Digital Dark Ages sets out to explore the intricacies of wider systems that feed into the idea of digital preservation while also questioning the ethics and parameters of archiving: what should and what should not be preserved for future generations? Departing from the more traditional investigations aimed at preserving the immaterial digital content which determine and record our lives, Digital Dark Ages embarks on a journey of explorations aimed at uncovering alternatives to past digital preservation strategies.

The emphasis on creating strategies dedicated to preserving the immaterial, does not come as a surprise. Since the early days of digital culture, we have been subjected to a relentless promotion of its potential. From the cybernetic poetics of the mid 1980s portrayed by William Gibson in Neuromancer (1984) to the latest innovations in augmented reality, we have always been invited to interact with the digital in its immaterial expressions. The actions of sending emails, streaming content and navigating the Web to look for any possible kind of information have now become our second nature. Most of our daily activities rely on immaterial systems, and even if we need physical devices in order to perform them, our interest towards them is limited to their design, power and reliability. We need these devices to get the job done, and once they become outdated or break, it is more convenient to buy a new device rather than look after obsolete software or repair it.

There has been little public awareness about the connections across what has been promoted as immaterial and the materials with which these devices are built. Between the immediacy of the interaction with the digital device’s interface – as the site where the information we retrieved online becomes visible – and the infrastructure on which this information travels. A call to re-establish a link between the immaterial and the material can only expand what we already know about digital decay into unknown territories. For instance, data decay or data rot is immediately visible to us as its consequences appear on the interface, but what happens beyond the surface of the digital device? Is digital decay an underlying condition that affects the digital device beyond our interaction with its immateriality?

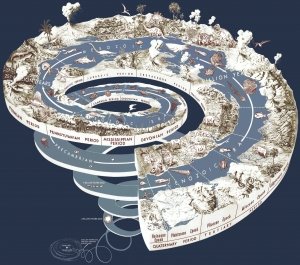

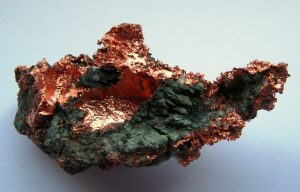

If we dig inside our smartphones, tablets, laptops, or fitbits, we’ll find the metals, ores and minerals on which information travels and is stored. In his book, A Geology of Media (2015), Jussi Parikka refers to digital materials as geological substrate. The connections between digital culture and geological materials become evident in Digital Dark Ages, an exhibition that questions our understanding of the digital by installing the artworks in the Treak Cliff cavern in the Peak District. Much of the cavern was formed by an underground river many hundreds of thousands of years ago. The group show provocatively overexposes the link between digital devices, geological formations and deep time or geologic time. It will be interesting to see how the works featured deal with the notion of ‘deep time’. The term ‘deep time’ was coined by Geologist John McPhee in his book, Basin and Range (1991) but has been re-appropriated by a generation of artists, writers and thinkers today, including Jamie Allen, Martin Howse, Siegfried Zielinski, Jussi Parikka and many more. Taking up a ‘deep time’ perspective means that longer histories may produce deeper meanings of the worlds in which we live. What ‘Deep Time’ also offers us is a way out of being trapped by progression or determinism, so we don’t have to think about digital archives but digital histories.

By way of investigating the geophysical qualities of digital materials, a provoking, more material idea of digital decay arises. I define digital decay as a form of material agency, a process to which no materials are estranged, not even the components of the digital infrastructure – often misunderstood as a purely immaterial system with unlimited possibilities in terms of storing, sharing and connecting. This idea of digital decay is detached from preservation initiatives such as Jon Ippolito’s Variable Media Questionnaire which aims at recording the artists’ intentions in order to preserve the artwork beyond the physicality of its media. It also offers more material approaches to explore Rhizome’s Net Art Anthology which, over a 2-year period, will restage, decontextualize and archive one artwork a week. Its aim is that of establishing a critical relationship with the limitations of digital culture, of rethinking the man-made construction of technological obsolescence, and of engaging audiences with current discourses on the Anthropocene.

Digital decaying materiality belongs to deep time. However, its consequences have already begun to interfere with humanity and nature. Leaking obsolete devices left to decay in e-waste dumpsites are toxic for the environment and represent a health hazard for human beings who, especially in impoverished areas of the world where these repositories are located, ‘mine’ the precious minerals and ore within the devices for little profit. These are just two examples that suggest that there is much more to digital decay beyond narratives of immaterial preservation.

Particularly relevant to exploring decay is what Shift Register is doing as part of their Earth Observatory Array Elements series. Their investigation aims at recording on obsolete devices the decaying signals emitted since the big bang. Rocks, obsolete technology and cosmic rays participate in this site-specific installation that links deep space, hard-drives, floppy disks and the geology of the cavern in an installation that I hope will inspire much more needed artistic interventions on to new ideas of digital decay and its atemporal connections with both today’s world and unknown futures.

The shorts in Rare Minerals reveal daunting aspects of digital infrastructure’s materiality: from data centres to abandoned mines, these artistic explorations invite the audience to reflect on the connections between the digital and the socio-economic and political discourses that define our globalised 24/7 world.

Everything In Slices Part V by Martha McGuinn speculates on the practice of archiving as fossilisation. Her machine is able to speed up fossilisation processes that from a deep time timescale now last a few days. The notion of future fossil is an interesting one as it evokes issues of obsolete media and e-waste, while also visualising the discarded device in its process of rejoining the planet’s ecological cycles.

Digital decay creates a link between human histories and the environmental scale of material ecologies. Although it operates on geological timescales, its effects on culture have become increasingly difficult to ignore. The decaying materiality affecting nature, and therefore by default humans, is able to reveal an unpleasant side of digital technology, far from the hype associated with technological advances as a necessary element partaking in humanity’s evolution. Challenging the old logic of human power over nature, artworks that engage with the foreseeable consequences of the materiality, left behind as obsolete, reveal that technology is not eternal and immaterial as it has been marketed to unsustainably generate profit.

This short article is an open invitation for the AND audience to consider such an idea of decay when visiting the festival. In my practice, I actively seek to rethink curatorial strategies for digital art in relation to the material turn. Through the curation of machines will watch us die (The Holden Gallery – 13 April/25May 2018), an informed idea of digital decay – repositioned within deep, geological space-time coordinates – will be explored as a material process partaking in ecologies of environmental duration.

Patrizia Costantin.

18 September, 2017

Patrizia Costantin is a curator and PhD researcher at Manchester School of Art (MMU). Building on media archaeology, she is researching the concept of digital decay through a ‘material turn’ in curatorial strategies for digital art. She is currently curating machines will watch us die (The Holden Gallery, 13 April/25May 2018),an exhibition exploring digital decay as an idea that revolves around processes of environmental formations, timescales of non-human nature and the debris of digital culture.

@PattiCostantin

Featured image: Rosemary Lee, Disc Rot from the series Molten Media, 2016.

Recent Journals

- Announcing our THREE FIELDS artists

- New Rhythms

- Introducing Commons // Keiken and Jazmin Morris

- Introducing our Creative Associates programme

- Reflections on the Associate Board Member Programme

- The Future of Arts Governance

- Rendering our virtual, net and digital discourses

- Announcing a new partnership between AND and the School of Digital Arts

- Impossible Perspectives 2024

Other Journals

-

2025

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

2019

-

2018

-

2017

-

2016

-

2015

-

2014

-

2013

-

2012

-

2011